Our Amnesia Plot

We do not know who we are or what we are for and this is by design. Cui Bono?

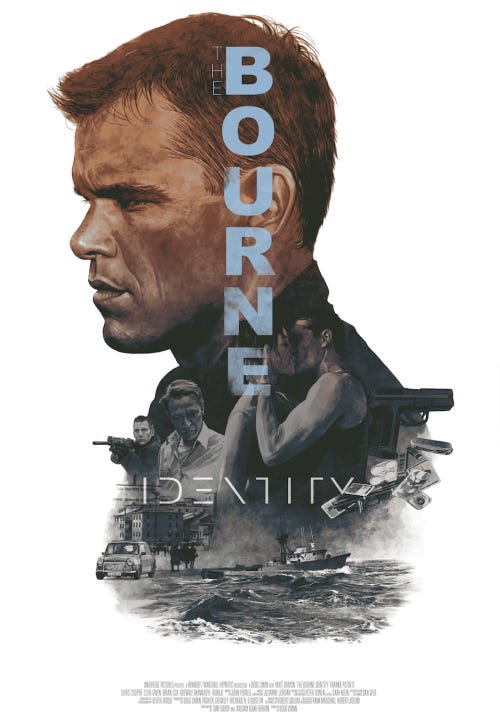

One of my favorite movies is The Bourne Identity, the action-thriller from the early noughties starring Matt Damon. The shot up body of a nobody is fished out from the middle of the ocean, a few clicks away from death. He’s rescued, and despite displaying extraordinary powers of language and self-defense, they realize he has amnesia. He does not know who he is or where he is from. The only clue is a small electronic device implanted in him with a safety deposit box in Zurich. Watch the movie. It’s good.

Though amnesia doesn’t really work this way, I believe it’s salience points to a deep sense that we have a buried and un-remembered past, somehow. We seem to know that we find ourselves within a story that has already started and that we have a real sense that we need to figure some things out.

Socrates gets into this notion of felt amnesia in various places, including the ever-relevant Meno dialogue. Socrates explores the notion of the immortality of the soul, that knowledge is somehow remembered or retrieved from some kind of earlier existence. But here I am, invoking Old Books and Old Movies. I’ll get back to this later on. The point now is that this film about a highly trained, highly capable CIA agent who has lost his identity remains strangely resonant. The movie unfolds by his re-collecting his own plot, which happens to be part of a much larger (and in his case) sinister reality, filled with CIA dark ops and political assassinations. What else would a lethally trained special ops guy be used for anyway?

What if the Amnesia was not an accident, but something done on purpose?

We’ve Been Amnesia’d

I contend that we are living through such a thought experiment. What would happen if we were cut loose from our inheritance? What would happen if we were somehow unburdened by what has been?

We have been unbuckled. We have been “thrown”. We have been amnesia’d. The mostly unspoken paradigm of contemporary education is progressive in outlook and design. The grand pooh-bah of our teachers’ teachers is John Dewey and his disciples. The guiding spirit of education for the better part of a century has been progressive in orientation and methodology. Education according to our gurus, should be “relevant” and “practical” because human potential has been artificially held back by dogged adherence to what has been. Wisdom, in this frame, is the enemy because wisdom is synonymous with bigotry and backwardness. The great promise of the 19th century progressive was to eradicate all the bad stuff and usher in all the good stuff. It is a version of the Church of Christ without Christ.1 And through the 20th and into the 21st this spirit is not only alive, but poised to complete its mission.

With a healthy assist from media and technology companies, our schools have successfully cut off two or three generations from the collective body of the world’s wisdom—all that has come before them. We have cut them off from their origins, and inoculated them from searching for their inevitable existential questions in that “other country” we call the past.

We have unburdened our children from what has been. We have lost our story.

Generations Zero

There is nothing that has come before us. We have no perspective. For instance, we just lived through a “Godwin’s Election” where the closing case of one candidate was to smear her opponent and her opponent’s supporters as Hitler. Of course, if that were true that would be really bad. Hitler was a bad guy, of course. But part of the joke about Godwin’s Law, the internet famous notion that “as an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches” is that we no longer have any other frame of reference. You are either a Nazi or you are a good person. Good people do not like Hitler or Nazi’s, therefore you must do anything in your power to disassociate yourself with all things Hitler and Nazi.

But what if the comparison is not true? What other examples might we find? Where would someone go to find such things? We have now generations of people who’ve been kept from the very source from which our comparisons and analogies flow. I use “Old Books” as my metonymy for the collective body of the world’s wisdom. If you are at all educated in the old fashioned sense you know that history and literature are replete with more apt comparisons, those peculiar things that we use in order to judge the present moment. We should read and thus know what has come before us so that we have something by which we can make sense of what is currently going on. If you want to read more about this notion, check out C. S. Lewis’ “Learning in Wartime.”2

So let’s get to the real crux of the issue for me, what I call the Cui Bono frame: who stands to benefit from the accomplishment of reforming education so that subsequent generations are artificially inoculated from knowing Old Books?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Underneath to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.